Click here for the interview with Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal.

BLINDSPOTTING is a contemporary fable told in dynamic syncopation and unexpected compassion as it uncovers the farce and tragedy of an Oakland in transition. As told by co-stars/co-writers/lifelong friends Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal, it explodes with visual energy and assured narrative power that understands that less is more when it comes to exposition, and that the perfect image can haunt us forever.

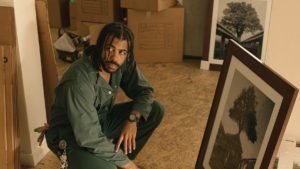

Daveed Diggs, Rafael Casal

The action covers three days, but not just any three days. These are the last three days of probation for Collin (Diggs), a spontaneous slam poet and essentially decent young man of African descent who was convicted of an unspecified felony and who has, until now, managed to keep his 11pm curfew at his halfway house, avoid any altercations with the cops, and maintain a job. He has the support system of lifelong best friend Miles (Casal), the white guy who is Old School Oakland to the marrow of his bones and just a little too quick with his hair trigger. They banter on the job moving furniture at the company where Collin’s ex, Val (Janina Gavankar) works, and off the job giving and getting the good-natured teasing that only guy who have known each other since they were 11-years-old could achieve. But there is a small bone of contention that will become larger as the story progresses, starting with Miles’ disgust at the gentrification of his favorite fast-food joint, and Collin appreciating the way the potatoes are cut in wedges now, instead of long fries. Has that world-view always been there, or has the shock of incarceration and probation changed Collin? Certainly the literal run-in with a running black man late at night, and seeing him gunned down by a white police officer affects him, but not in the way everyone in the audience would expect. With three days to go on his probation, and a realistic assessment of his situation, he does not report what he saw. His reasoning is neatly summed up by Collin to Miles with the deadpan irony that is at once wildly funny and equally heartbreaking. It’s a conversation that flows into Miles’ disgust at the $10 juice that his corner market now carries, and the bemusement that Miles is buying it.

This is the genius of this film. Any moment, any situation, can go from comedy to catastrophe, be it a moment of quiet revelation, or a violent brawl where teeth are broken and blood flows freely. The droll observational humor is perfectly balanced with moments of absolute horror, a move that works despite being so counter-intuitive that is might constitute an entirely new genre. As these characters work out feelings that have been simmering for years, the sorting becomes a metaphorical blood bath, all the while Diggs’ gift for evoking empathy with his subdued performance of subsumed rage grabs us by the throat and the funny bone, forcing us to see things from a new point of view. He catches with chilling clarity the fear that accompanies a walk after dark with the police on patrol, and the pain borne of his unresolved issues of race and class with Miles, who is grappling with his own issues of identity as these two men, each with a big heart, both battle demons not of their making. And try to find a way to talk about it that doesn’t destroy them.

BLINDSPOTTING explores race, class, and perceptions with an astute and unflinching eye as it also provides an  elegy for the Oakland that was. That last is perfectly embodied by Wayne Knight as the wistful photographer bent on commemorating the old Oakland by superimposing images of oak trees on landscapes where they used to be, and preserving the faces of the inhabitants shortly to be displaced by moneyed newcomers. The cameo is, in its own way, as poignant as the gutted house that Colin and Miles are tasked with clearing of debris, only to be stopped for a moment by a forgotten family album that is, ultimately, added to the heap of things destined for the dump. And it’s as telling as the question Miles puts Ashley (Jasmine Cephas Jones), the woman with whom he is giddily in love, about her determination to send their son, with whom he is equally smitten, to a more expensive, bi-lingual school. Isn’t it enough that he’s biracial, he asks before getting on board. The future is an unknowable amalgam, with only the ability to cross the divides to make it a good one.

elegy for the Oakland that was. That last is perfectly embodied by Wayne Knight as the wistful photographer bent on commemorating the old Oakland by superimposing images of oak trees on landscapes where they used to be, and preserving the faces of the inhabitants shortly to be displaced by moneyed newcomers. The cameo is, in its own way, as poignant as the gutted house that Colin and Miles are tasked with clearing of debris, only to be stopped for a moment by a forgotten family album that is, ultimately, added to the heap of things destined for the dump. And it’s as telling as the question Miles puts Ashley (Jasmine Cephas Jones), the woman with whom he is giddily in love, about her determination to send their son, with whom he is equally smitten, to a more expensive, bi-lingual school. Isn’t it enough that he’s biracial, he asks before getting on board. The future is an unknowable amalgam, with only the ability to cross the divides to make it a good one.

Your Thoughts?